One of the perhaps most problematic parts of any work on diversity issues, be it in form of DEI efforts for businesses and NGOs or indeed any work on national and international minority rights is that it is subject to many kinds of Othering. Without Othering, without bias, we would not even need to have this conversation; unfortunately, as you are probably aware, diversity issues are very much a necessary conversation to have because Othering does, simply put, exist in many ways and forms.

There are several ways one can Other, and they depend on many factors – legal framework of a country, for instance, may be set up to deliberately or incidentally (when following from older, deliberate, framework because of a desire for cultural or social continuity); then there is the negative Othering (that we often talk about) that is expressed in forms of microaggressions and bullying, and the positive Othering that is expressed by eg a set of expectations we hold about someone due to their identity or an aspect thereof (eg all Jews are great musicians, all Black people are great dancers, all gay men have a wonderful fashion sense, all lesbians know how to fix things, all men are reliable in a crisis, all women are nurturing…).

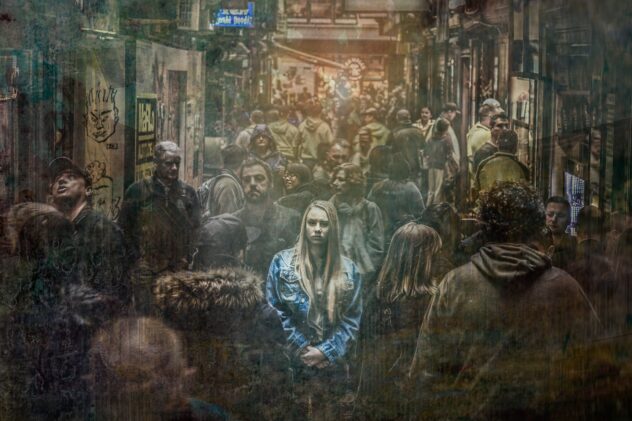

But there is one other type of Othering that generally isn’t discussed much…and that is the Othering of misfits.

WHAT IS OTHERING OF MISFITS?

In a sense, this type of Othering exists as an offshoot of positive Othering. But it’s slightly more complicated.

When someone is Othered as a misfit, they:

– have or are perceived to have a specific identity (eg are gay or are perceived gay)

– the way they express their identity or fail to express it is not how their identity is thought of; a lack of expression – for various reasons – may be perceived in the same way

– not fitting to the idea of who they are supposed to be is taken as a personal issue by someone – perhaps a younger diversity officer or a colleague who deems themselves an activist – and as a result, they will attempt to push the person into fitting, “revealing” their “true” identity or for that matter insisting, even aggressively, that this identity exists.

In simple terms, the fact that the person doesn’t fit the expected criteria is taken, implicitly or explicitly, as an affront.

WHY?

The reason is actually simple. In our time, with greater and greater polarisation, and with very little grey area between acceptance and total social banning, the pressure to be “perfect” is at a peak…and a part of this perfection is to be a perfect actor socially – a perfect ally, perfect anti-racist, etc.. However important these notions are in practice, they can also become a mantle of perceived and strived for “goodness”, a check-list, if you will, of one’s social/group acceptability. If someone behaves differently, they are essentially stripping a person of being able to showcase their expected goodness in practical terms in their environment, which, in turn, becomes stressful, and the person may lash out, including by in a sense bullying the “originator” of their plight in some way, partly to alleviate frustration but mostly because they want to elicit an expected response that would “prove” their goodness through establishing the expected interpersonal behaviours. In other words – one cannot show that they are, eg, a good ally, if the man in question fails to act like a stereotypical gay or even fails to admit they are one. Very publicly, we see that in the questionable demand for public persons to be open about their sexuality; some are, some are not, but all should technically have the right to be as open or not about it as they choose, something that the gay liberation movement tried to achieve for decades. Coming out is and should always be a choice, and while it would be a great world in which nobody would feel unsafe to come out, it is also true that talking about one’s sexuality is still a personal choice even for cis-gendered heterosexuals.

This is just one, albeit very clear, example of such behaviour. In terms of race, responses to trauma or personal experience (or lack thereof) can elicit similar behaviours; in terms of sex/gender, especially women will often be pressed by other women to open up about (it confirm the stereotypical expectations of) mistreatment by and fear of men. Even if the person in question has experienced that, and the same goes for racial trauma, no one should be pushed into discussing or reliving it simply because it fits a narrative another person would like to see their actions through.

In many cases, especially of sexual minorities, but also of minority-related and gender-based violence, people may also be unwilling to discuss their experiences or identity because, for many years, keeping quiet has been their lifeline, or the discussion is taboo for them for some reason. Either way, pressing them to express their identity in a desired way can be very traumatic, a complete opposite of what DEI efforts – which should include psychological safety – are all about.

Then, there are cases of mistaken identity. People who may “seem”, who fit a stereotype, may not in fact have that identity, but will have to fight to have their true identity restored. A very quiet, well put together, gentle man may not be gay, however much he “seems” to fit the stereotype; a dark-Mediterranean Italian is not Black, but may be perceived as Black and expected to behave as if they are, whereas a very fair-skinned Black person may be vilified if they act Black. A very nurturing, naturally caring woman may be pressured to “feel safe to be a feminist” as if there is only one way a woman can ever be nurturing and caring, and that is through acts of oppression. The list goes on.

THE PROBLEM ISN’T YOU – IT’S THE OTHER PARTY

For people who experience this type of Othering, where they are essentially considered Other because they are not Other enough, or they are too Other for what is expected of them, the whole situation can seem very daunting and painful. That is because we know how to deal with bias, we know how to deal with bullying and sexual violence, we know even how to address positive bias…at least in theory, these are more or less discussed and there exist societal and often legal repercussions for the behaviours of the perpetrators.

But how do you explain to anyone, including yourself, that a person is trying to push you into a mould because of what they think you should be like according to how they understand your identity…an identity that they may also be utterly wrong about? How do you stop a person who acts well-meaning to some extent, but who may get increasingly pushy, and who may be asking others to “help you”, spreading their version of you around?

This is not discussed much at all, in part because we are often unwilling to see that even good intentions can turn toxic under certain circumstances.

SO WHAT DO YOU DO?

There is no one simple solution, but here’s something we all can do – remain aware that bias doesn’t always look the way we expect it to look. If we are to make workplaces – and ultimately our society – truly diversity friendly, then we should remember that feeling we had as children when we really wanted to do something, and then someone else sighed impatiently and too it all out of our hands.