One of the best things about social and cultural anthropology is that it can literally touch any topic. For me, that means I get to write about (and research) literally whatever I want when not working on a client specific question.

This also means that, whatever you look at, technically is anthropology. (Hence the name of this page… Anthropology is everywhere).

While anthropology is becoming more and more diverse and specific (such as technical anthropology, working on ethnography specific to newest innovations), you can’t beat the social and cultural anthropology – in a way, it’s already got everything that everyone else wants, and some. So while the specialisations are fascinating, there is always necessity for the basics – and that’s where we hit the social and cultural.

And today’s topic really reflects that.

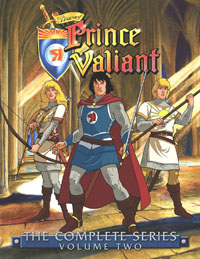

We’re going to be talking about Prince Valiant.

The 90s cartoon series on Prince Valiant, to be exact.

Don’t even ask why and how two grownups ended up watching the ENTIRE two seasons in a few weeks’ time. (But we did. 🙂 )

While this is a series that was out roughly in time for our growing up, we both missed it, until I was looking at information on something else entirely and ended up bumping into information that led me to comics and newspaper cartoons of the early twentieth century, and from there to Prince Valiant as a concept, and from there to the series, and then, I suppose you can imagine the rest.

The truth is that I find representations of older myths absolutely captivating. Myth is how we communicate across the distance of time and space. It may reflect actual events, indoctrination patterns or simple tales someone made up at some point for who knows what reason… and there’s fanfiction of it.

Yes, you heard right… because that’s what many tales are, a fanfiction of something else.

Arthurian tales are a gorgeous example of fanfiction. It’s tough to say when they started; historians deem them to have possibly started somewhere around 6th to 7th century, and they are mingled with other tales… Charlemagne, otherwise a historical person (cf. here) (whereas Arthur and his knights and enemies are not likely to have existed (cf. here)), and his knights get pretty much intertwined with the Arthurian myth in no small manner, as do many Welsh and Cornish myths (cf. for example – Orlando Innamorato and Orlando Furioso).

At the same time, Arthurian legends have been revisited often in later eras, from the later contemporary authors such as Chretien de Troyes to the Victorian revival, which modernised and romanticised much of what was perhaps less “knightly” and gave us the greater part of what we deem to be Arthurian myth today… such as the relationship between Guinevere and Lancelot, presented so iconically by Robert Taylor and Ava Gardener, which becomes platonic rather than sexual, where it once read:

“Lancelot and the queen took their pleasure until dawn” (cf. footnote 1)(Mental note to self – wow… 🙂 ).

Prince Valiant is not as such an original Arthurian figure. He was invented, on basis of romanticised Arthurian legend, by Hal Foster in 1932, and the story, in its comic strip form, is still ongoing (cf. here, here & here). He is, however, especially in the cartoon form, a good introduction to the topic for anyone; the notions of chivalry, especially the romantic chivalry of the 19th century perception, as well as the completely personal struggles of the characters are brilliant for any age and for any knowledge of the shall we call it original story arc.

The premise is simple – the young Prince Valiant receives, in a dream, a vision of Camelot, the height of chivalry and humanity that he does not even truly know exists at that point. After an enemy ousts his family and himself from their little kingdom of Thule, the prince ends up living a simple life – which he resents terribly – in a swamp, which he leaves, without the agreement of his father but with support of his mother and mentor, to look for Camelot.

On his way, he encounters two companions that become not only travel buddies but a core of the story and Valiant’s life at Camelot – Arn, an orphaned, survivalist peasant, and Rowanne, a blacksmith’s daughter, who, despite being in a bit of a tight spot when they first encounter her, is a no-nonsense maiden who is well suited to taking care of herself, and an excellent markswoman with a crossbow and bow.

These two begin to share Valiant’s dream pretty quickly, and the three set out together to finally find Camelot after many adventures halfway through the start of the first season.

They become a part of the court and all three – regardless of sex/gender and social standing – aspire to knighthood, which, unusual indeed in the case of the other two and a logical step for Valiant, they are allowed to pursue and they are treated equally throughout the story.

From there on, the plot begins to include more usual Arthurian elements, such as Merlin and Morgana as opponents (although Mordred is, in this version, Arthur’s old friend and Morgana’s lover (or one of them), not son like is some versions of the tale – cf. here), seemingly impossible and dangerous tasks and journeys to half-mythical places (e.g. Avalon), as well as the elements from the original Prince Valiant series.

At the same time, it features, more and more, character struggles and little lessons that are highly important to consider. Strife, for instance, comes at a cost, and in at least two instances, the plotting fathers end up accidentally killing their own sons when seeking to kill someone else; social class is addressed impeccably, along with several points on fair and unfair behaviour, both from peasants and from nobles; racism is given a not so brief study when Sir Bryant, a character specific to the tale of Moorish descent is accused of treason mostly due to his colour; women’s rights and equality are a constant staple of most tales.

At the same time, the story features immensely strong female characters; so strong in fact it is odd that they have been so utterly overlooked by most. Rowanne is a capable warrior and blacksmith; she is as good as the men with the sword and on horseback, and a million times better with the bow and arrow. For most of the plot, she switches between male and female clothing – just as the men switch from hunting or travel clothes to regalia. Aleta, Valiant’s true love and later betrothed, is pretty much a warrior princess, trained in warfare and good at it; her clothing, as well, is usually masculine unless in very specific contexts, and she is frequently portrayed in full armour.

Queen Guinevere (the story excludes Lancelot and their relationship from the series completely, and the King and Queen are portrayed as a loving, affectionate couple) is a wise and caring person; while she mostly remains distinctly feminine in a classical sense, she does exchange her gown for armour at the end, and leads the army, at times without the specific guidance and help from the men (other than the same her husband and Prince Valiant receive). Morgana, the great seductress and enchantress, is a capable woman, at times nearly besting her opponents (including Merlin), and so are many others portrayed in a similar way, regardless of how feminine or not they appear.

The original Arthurian tale and its spin offs are not utterly devoid of strong female characters; in many ways, the male characters are often portrayed as decidedly weaker than the female (with many knights falling prey to anything from seduction to magic and more), with or without their martial aspect included… And as we can see with the portrayal of Bradamante (as well as disputably many other, less fictional personas), that martial aspect is not completely impossible for a female. History and myth both recount many powerful women, including warriors (with the latest being a female Viking warrior, whose status and sex have been proven scientifically) (cf. here). But we have somewhat forgotten them, because they were either ignored or tamed down considerably in Victorian era, and by early to mid twentieth century, which subsequently led to a revival of strong and active female characters in many tales and especially cartoons.

Watching the series was a lot of fun, in many ways. What was possibly most immense as a message was that Rowanne, for all that Arthur pauses when he knights her, and is unsure of how to address her, uncertain if “Sir” would fit, struggles far less than Arn, whose feelings of worthlessness due to his social status frequently make him feel at odds with the world, causing him to bumble even more than Valiant, who is, initially, a truly messed up character, somewhat resemblant of the worst character traits of Scott’s Ivanhoe (which are usually overlooked, and were somehow supposed to be perceived as positive – in the original, Ivanhoe is visibly interested in breaking his word of fidelity to Rowena but loses interest when he realises that Rebecca is a Jewess, and henceforth treats her with ill-masked contempt in all ways; his readiness to help her during her trial is very clearly not because of her peril, or even some vague feelings of gratitude he should have felt for her saving his life, but because he sees a ready chance to battle the Templar that he simply cannot pass up; even after he is married to Rowena, he is implied to have often thought of Rebecca).

While the series only lasted two seasons, it touched many topics that are of interest to us nigh twenty years later. If you have the time, go watch it – it’s not a bad way to pass some time in exploring the concept of Arthurian legend as much as those concepts that make us human.

Footnotes:

1. Malory, T. (1485) Le Morte D’Arthur

All links accessed between 30th April – 1st May 2018